Alexei Navalny’s memoir, in particular, reminds readers how crucial the freedoms to vote and dissent are.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

If I were to assign one book to every American voter this week, it would be Alexei Navalny’s Patriot. Half memoir, half prison diary, it testifies to the brutal treatment of the Russian dissident, who died in a Siberian prison last February. Still, as my colleague Gal Beckerman noted last week in The Atlantic, the writing is surprisingly funny. Navalny laid down his life for his principles, but his sardonic good humor makes his heroism feel more attainable—and more real. His account also helps clarify the stakes of our upcoming election, featuring a Republican candidate who has promised to take revenge on “the enemy from within.”

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

Now, if I had enough time to assign voters a full syllabus, Ben Jacobs’s new list of books to read before Election Day would be the perfect starting point. Literature on campaigns of the past offers a “well-adjusted alternative” to doomscrolling or poll-refreshing, Jacobs writes, recommending five works that put the madness into much-needed perspective—including H. L. Mencken’s account of a raucous Democratic convention; Hunter S. Thompson on fear, loathing, and Richard Nixon; and a deep dive into the chaotic 2020 presidential transition.

Navalny’s memoir takes place under a very different political system, but it, too, covers presidential campaigns, including his own attempt to challenge Russian President Vladimir Putin (Navalny was ultimately barred from running), as well as plenty of other chaotic leadership transitions (from Mikhail Gorbachev to Boris Yeltsin to Putin). These are not the convulsions of a mature democracy—today, Putin rules as a dictator—but in Navalny’s unrelenting good nature, there are glimpses of what a Russian democratic leader might look like. (He might be a Rick and Morty fan; he might build a functional legal system.) Embedded in this martyr’s story—what Beckerman calls “the passion of Navalny”—is the tragedy of a world power that missed the chance to build the kind of open society Americans now take for granted at their peril.

The most fundamental freedom of an open society may be the right to vote, even when, as in the United States, the choice is constrained by a two-party system and the rules of the Electoral College. In a perfect world, perhaps a protest vote wouldn’t be a wasted one, as Beckerman noted in another story this week; a ballot wouldn’t count more in Pennsylvania than in New York; a presidential choice wouldn’t have to be binary. But Patriot reminded me that Navalny also voted—knowing it was futile. He tried to run for office, knowing he’d be punished for it. And he kept speaking out from prison, knowing he would likely die for it. He did these things out of optimism. He thought his country would one day be free: “Russia will be happy!” he declared at the end of a speech during one of his many show trials. If he could believe that, then Americans, whose rights are more secure but not necessarily guaranteed, can be optimistic enough to vote.

A Dissident Is Built Different

By Gal Beckerman

How did Alexei Navalny stand up to a totalitarian regime?

What to Read

The Red Parts, by Maggie Nelson

In 2005, Nelson published the poetry collection Jane: A Murder, which focuses on the then-unsolved murder of her aunt Jane Mixer 36 years before, and the pain of a case in limbo. This nonfiction companion, published two years later, deals with the fallout of the unexpected discovery and arrest of a suspect thanks to a new DNA match. Nelson’s exemplary prose style mixes pathos with absurdity (“Where I imagined I might find the ‘face of evil,’” she writes of Mixer’s killer, “I am finding the face of Elmer Fudd”), and conveys how this break upends everything she believed about Mixer, the case, and the legal system. Nelson probes still-open questions instead of arriving at anything remotely like “closure,” and the way she continues to ask them makes The Red Parts stand out. — Sarah Weinman

From our list: Eight nonfiction books that will frighten you

Out Next Week

📚 Carson the Magnificent, by Bill Zehme

📚 Lincoln vs. Davis: The War of the Presidents, by Nigel Hamilton

📚 Letters, by Oliver Sacks

Your Weekend Read

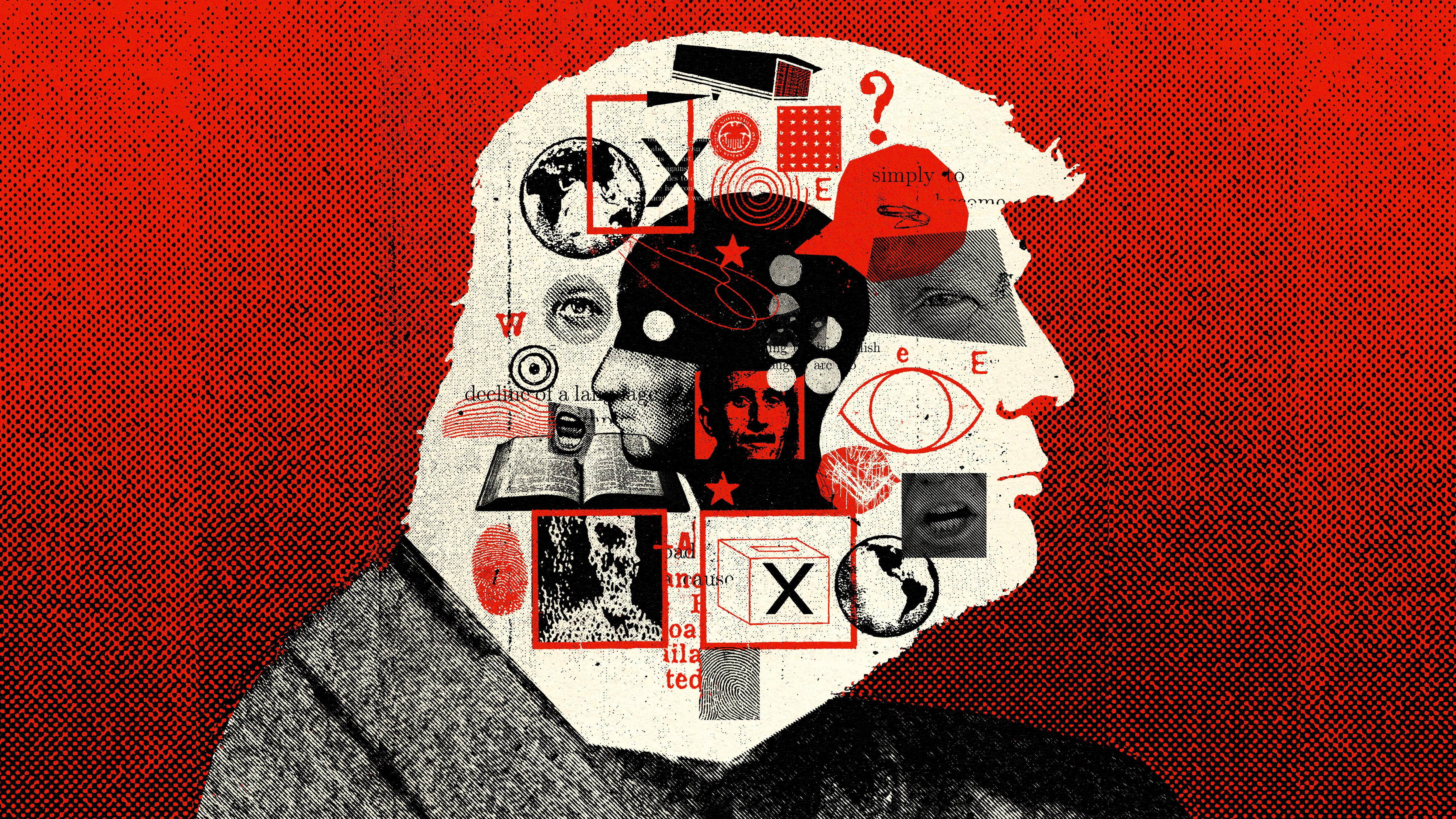

What Orwell Didn’t Anticipate

By Megan Garber

“Use clear language” cannot be our guide when clarity itself can be so elusive. Our words have not been honed into oblivion—on the contrary, new ones spring to life with giddy regularity—but they fail, all too often, in the same ways Newspeak does: They limit political possibilities, rather than expand them. They cede to cynicism. They saturate us in uncertainty. The words might mean what they say. They might not. They might describe shared truths; they might manipulate them. Language, the connective tissue of the body politic—that space where the collective “we” matters so much—is losing its ability to fulfill its most basic duty: to communicate. To correlate. To connect us to the world, and to one another.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.